In the first half of 2011, the United States Supreme Court decided a trio of securities class action cases, and what may be the most significant class certification decision in several decades; new case filings continue to trend upward; and major “credit crisis” cases are beginning to be resolved

The first half of 2011 has been a significant time for private securities litigation. As anticipated in Gibson Dunn’s 2010 Year-End Securities Litigation Update, the United States Supreme Court decided three important cases: Siracusano v. Matrixx Initiatives, Inc., Erica P. John Fund, Inc. v. Halliburton Co., and Janus Capital Group Inc. v. First Derivative Traders. Matrixx and Halliburton, respectively, provide new guidance to trial courts on materiality and class certification issues, while Janus settles once and for all that a person cannot be liable in private securities lawsuits for “making” a misleading statement or omission unless he or she had ultimate authority over its content and communication to others. In addition, in Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Dukes, the Supreme Court reversed certification of the largest employment discrimination class in history, in a ruling that is likely to have profound implications for securities class actions. This series of Supreme Court decisions is certain to have a lasting effect on securities class action litigation, and reshape how these cases are litigated in the future.

While the Supreme Court has shown keen interest in securities cases over the last few years, the Court’s rulings do not appear to have slowed the pace of private securities litigation to any significant degree. Indeed, according to a new study by NERA Economic Consulting, new securities class action filings continue to be on the rise in the first half of 2011, after a measurable increase in new case filings in 2010. From the beginning of this year through the month of June, plaintiffs have filed 130 new federal securities lawsuits, an uptick of almost 30% over the number of cases filed during the same period last year. NERA projects that 260 such cases will be filed by the end of 2011–the highest number in nearly a decade.

The first half of 2011 also saw several other developments that are likely to have an impact on private securities litigation. Among other things, the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) promulgated the Whistleblower Rules under the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (“Dodd-Frank Act”), which are likely to spawn a new generation of private cases fueled by the “bounties” being offered to whistleblowers under the new rules. Securities litigation also shows every sign of going global, as the number of cases filed in foreign countries is accelerating. Meanwhile, here in the United States, foreign issuers continue to be sued despite the Supreme Court’s decision in Morrison v. National Australia Bank, which held that Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange of 1934 (“Exchange Act”) does not apply extraterritorially to investor claims against foreign issuers involving foreign conduct.

Some of the most significant case law and legislative developments in the first half of 2011 are summarized by category below.

Table of Contents (click on link)

II. Supreme Court Developments

A. Janus Capital Group Inc. v. First Derivative Traders

B. Siracusano v. Matrixx Initiatives, Inc.

C. Erica P. John Fund, Inc. v. Halliburton Co

D. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Dukes

E. Simmonds v. Credit Suisse Securities

III. Jurisdiction Of U.S. Courts Over Claims Against Foreign Issuers After Morrison

IV. “Credit Crisis” Litigation

A. New Case Filing and Decisional Trends

B. Credit Crisis Settlement Trends

VI. Important Class Certification Rulings

A. “Price Impact” Arguments Against the Fraud-on-the-Market Presumption

1. Erica P. John Fund, Inc. v. Halliburton Co

3. In re Moody’s Corp. Sec. Litigation

VII. Other Major Issues Addressed By Trial Courts on Motions to Dismiss and Summary Judgment

B. Pleading and Proving “Scienter” or State of Mind

C. Use of “Confidential Witnesses” to Plead Securities Fraud

VIII. SEC and DOJ Enforcement Trends

A. New SEC Enforcement Actions in 2011

IX. Legislative Update — New SEC “Whistleblower” Rules Under The Dodd-Frank Act

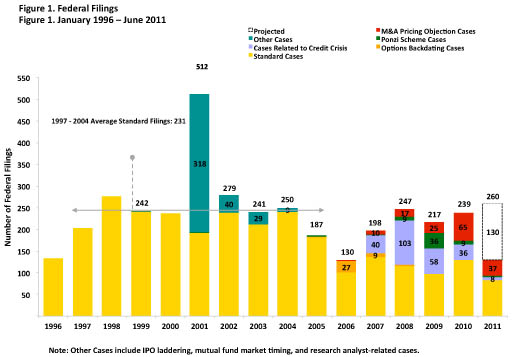

According to a study by NERA Economic Consulting issued on July 26, 2011,[1] filings of new PSLRA class action suits in federal court are on the rise. Filings in 2010 were higher than in 2009, and indeed higher than in any year in the last five years except 2008, which was marked by a large number of “credit crisis” case filings. As Figure 1 reflects, 2010 case filings included more “standard” PSLRA cases than in any year since 2007. This year’s filings are trending further upward. In the first six months of 2011, plaintiffs filed 130 new federal securities class actions. If plaintiffs file the same number in the second part of the year, the total of 260 would exceed that of any year since 2002. Standard case filings are trending toward 166, which would be the highest number since 2005 (all charts courtesy of NERA Economic Consulting):

The increase in “standard” cases can be attributed in large part to a new wave of lawsuits arising from reverse mergers by China-based issuers. NERA reports that in the first six months of 2011, plaintiffs filed 27 lawsuits against China-based companies. Those lawsuits account for 60% of the federal filings against all foreign-based companies in that period.

NERA also determined that the level of new cases filed in 2010 involving objections to M&A transactions spiked considerably over the previous years. In Figure 1, NERA projects that new case filings for 2011 will exceed 2010 levels, and that the level of M&A pricing objection cases at mid-2011 is trending to be even higher for the full year 2011 than in 2010.[2]

NERA observed that the Ninth Circuit is maintaining its dominance as the home circuit to the highest number of new filings. The Second Circuit led the nation in new filings from 2006 through 2009. The Ninth Circuit overtook the lead in 2010 and is holding its position so far this year. As reflected in Figure 3, 40 new federal securities class actions were filed in the Ninth Circuit during the first half of 2011, compared to 32 in the Second Circuit. See Figure 3 of NERA’s study, Federal Filings by Circuit, Year, and Type of Case, January 2006 – June 2011.

Average settlement amounts have varied widely over the past several years. As Figure 21 reflects, the average settlement in 2009 amounted to $14 million. That average surged in 2010 to $108 million. In the first half of 2011, average settlement values declined steeply to $23 million. This year’s average is currently well below the average for the entire period from 2002 through June 2010, which amounts to $42.8 million. See Figure 21 of NERA’s study, Average Settlement Value ($MM), All Cases January 1996 – June 2011.

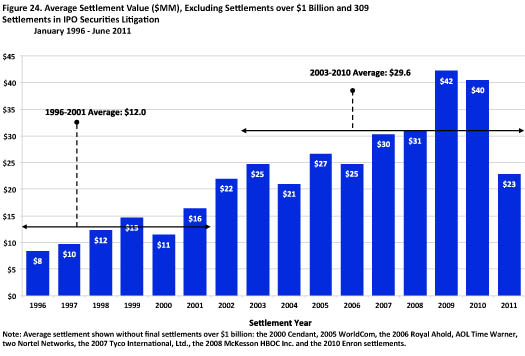

By adjusting the settlement statistics to exclude outlying cases, the trend reflects somewhat less volatility. Nonetheless, settlements in the first half of 2011 continue to be down significantly from 2010 levels. Excluding final settlements of more than $1 billion and the 309 settlements in the IPO Litigation in the Second Circuit, the average settlement value for the period from 2003 to 2010 was $29.6 million. The average for the same population of cases was far higher in 2009 and 2010–$42 million and $40 million, respectively. These statistics are reflected in Figure 24 of NERA’s study:

As shown in Figure 24, average settlement values for the first half of 2011 were down significantly from 2010 levels, $23 million versus $40 million. Even so, the average of $23 million generally is consistent with average settlements in the years immediately preceding the onset of the credit crisis in 2007. In the five-year period 2002 to 2006, average settlements were $24 million.

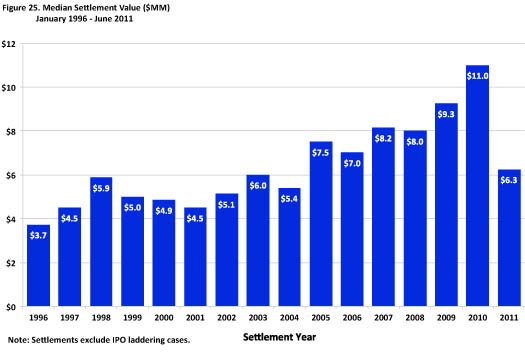

The trends in median settlements generally mirror the trends for average settlements, excluding the same outliers noted above. As reflected in Figure 25, NERA determined that median settlements in 2010 were up from 2009, $11 million versus $9.3 million. Indeed, the 2010 median settlement of $11 million is the highest recorded since 1996,the first year following passage of the PSLRA. For the first half of 2011, NERA determined that median settlements had declined to $6.3 million. Still, the median settlement of $6.3 million for the first half of 2011 is generally in line with the five-year median settlement for the period 2002-2006, which was $6.2 million.

For more information concerning cases arising from the “credit crisis” in particular, see Section IV of this update below.

C. Fee Awards Continue to Be Outsized, and the Major Plaintiffs’ Firms are Increasing Their Market Share

The aggregate dollar amount of fee awards to plaintiffs’ firms continue to stagger the mind. According to one recent study by NERA of securities class action settlements, in 2010 plaintiffs’ lawyers were awarded $1.492 billion in fees, close to the record set in 2007 of $1.704 billion in fees. See J. Milev, Trends 2011 Mid-Year Study, NERA Economic Consulting, at 27, Fig. 30 (July 2011). All of the ten largest settlements exceeded $1 billion and generated massive attorneys’ fees. Id. at 21. NERA reports that during the period from January 1996 through June 2011, the median fee award for settlements in excess of $500 million was 8.3% of the settlement amount. For settlements that ranged from $100 million to $500 million, plaintiffs’ lawyers reaped an astounding median of 22.2%. Id. at 27.

A handful of plaintiffs’ firms continue to dominate nearly all of the nation’s largest–and most lucrative–settlements. According to one report, the law firm of Bernstein Litowitz Berger & Grossman served as lead counsel in 28 of the 100 largest securities class actions to have settled since 1996. The Milberg firm (in its various incarnations) served as lead counsel in 26, and Robins Geller Rudman & Dowd (and its predecessor firms) in 13. Securities Class Action Services: The SCAS 100 for Q2 2011, Institutional Shareholder Services Inc. (July 2011).

Although updated statistics are still being generated for new settlements and fee awards in 2011, all indications are that the fees of plaintiffs’ attorneys will continue to rise and the largest settlements will continue to be concentrated among a small number of well-funded firms with deep connections to public pension funds.

The good fortune of the plaintiffs’ bar contrasts with the ratio of settlement amounts to average investor losses, which has been on a steady decline since passage of the PSLRA in 1995. In 2010, investors recovered in settlement just 2.4% of their losses. See Milev, Patton & Starykh, supra at 30. In the first half of 2011, that figure declined further to a paltry 1.0%. Id.

Perhaps because the dollar awards to plaintiffs’ counsel in PSLRA cases have become so large, trial courts have shown more willingness to scrutinize plaintiffs’ requests for large percentage fee awards. A 2010 decision illustrates this heightened review. In In re Dell, Inc. Sec. Litig.,[3] the district court was asked to award a fee of 25% of the common fund in connection with a proposed settlement of $40 million, which would resolve class claims against Dell alleging that Dell has misstated its revenues during the class period by almost $500 million, and causing alleged damages that “could have run into the billions.” The district court had dismissed the claims in 2008, and plaintiffs appealed to the Fifth Circuit. While the appeal was pending, plaintiffs’ counsel settled the case. Noting the “steep and perilous path Plaintiffs would have to climb” in order to recover anything for the class in light of its dismissal order, the district court overruled the handful of objections to the settlement to the effect that the $40 million recovery was too low. Nevertheless, the court concluded that a downward adjustment in the fee award from 25% to 18% was required, noting that 18% was the low end of the range of percentage fees that the institutional investor serving as Lead Plaintiff had negotiated with class counsel at the commencement of the case. The trial court specifically found that the time and labor involved weighed in favor of a downward adjustment, as did the skills required to perform the legal services adequately. Indeed, the court quite candidly stated that the legal services performed were inadequate, given plaintiffs’ inability to plead a proper claim: “[T]he results achieved by Lead Counsel in the litigation were undeniably poor.”

II. Supreme Court Developments The Supreme Court decided several cases in the first half of 2011 that promise to have a significant impact on private securities litigation. The Court also has accepted review of another securities case for the 2011-12 term, indicating that securities litigation will continue to be an area of focus for the Roberts Court.

On June 14, 2011, the Supreme Court in Janus Capital Group Inc. v. First Derivative Traders, 131 S. Ct. 2296 (2011), brought much-needed predictability to the securities markets by articulating a “clean line” separating “those who are primarily liable (and thus may be pursued in a private [Rule 10b-5] suit[]) and those who are secondarily liable (and thus may not be pursued in private [Rule 10b-5] suit[]).” Id. at 2302 n.6.

In a 5-4 opinion authored by Justice Thomas, the Court concluded that Janus Capital Management (“JCM”), a registered investment adviser, cannot be held liable in a private Rule 10b-5 suit for drafting allegedly misleading prospectuses issued by its mutual-fund client, the Janus Investment Fund. Instead, the Court made clear that the only proper defendant in a private Rule 10b-5 suit is the “maker” of the statement–“the person or entity with ultimate authority over the statement, including its content and whether and how to communicate it.” Id. at 2302. “Without control,” the Court explained, “a person or entity can merely suggest what to say, not ‘make’ a statement in its own right,” and therefore “[o]ne who prepares or publishes a statement on behalf of another is not its maker.” Id. (quoting 17 C.F.R. § 240.10b-5(b)).

Applying this test, the Court concluded that “JCM did not ‘make’ any of the statements in the [Janus Investment Fund’s] prospectuses”–even if it may have participated in the writing and dissemination of the prospectuses–because JCM’s involvement was “subject to the ultimate control” of the Janus Investment Fund. Id. at 2305. “There [wa]s no allegation that JCM in fact filed the prospectuses and falsely attributed them to Janus Investment Fund,” the Court noted, “[n]or did anything on the face of the prospectuses indicate that any statements therein came from JCM rather than [from] Janus Investment Fund–a legally independent entity with its own board of trustees.” Id. Accordingly, the statements in the prospectuses were made by Janus Investment Fund–not by JCM. Id. at 2304-05.

Although the opinion does not expressly address the liability of persons or entities other than investment advisers who provide services to public companies, those service providers–bankers, lawyers, accountants, financial advisers, and others–should be able to invoke the decision to defend private lawsuits based on their work behind the scenes in preparing offering documents for their issuer clients. The issuer–not the service provider–has “ultimate authority over the statement[s]” in its offering documents, and it is therefore the only “maker of [those] statement[s]” under the Court’s rationale. Id. at 2302.

The Court’s decision is also noteworthy because it casts doubt on the SEC’s continuing claim that it is entitled to deference on the scope of the Rule 10b-5 private right of action. Because the Court found no ambiguity in the term “make,” it declined to consider whether it should defer to the SEC’s interpretation.” Id. at 2303 n.8. But the Court went further to state: “[W]e have previously expressed skepticism over the degree to which the SEC should receive deference regarding the private right of action,” and this is “not the first time this Court has disagreed with the SEC’s broad view of § 10(b) or Rule 10b–5.” Id. These observations should lend support to those challenging the SEC’s interpretation of the private right of action, particularly when viewed in light of Justice Scalia’s recent suggestion that he would be willing to reconsider whether “an agency’s interpretation of its own regulations” is entitled to deference. See Talk Am., Inc. v. Mich. Bell Tel. Co., 131 S. Ct. 2254, 2265 (2011) (discussing Auer v. Robbins, 519 U.S. 452, 461 (1997)).

Gibson Dunn represented Janus Capital Group Inc. and JCM, and our partner Mark Perry argued the case before the Supreme Court.

On March 22, 2011, the United States Supreme Court issued a unanimous opinion affirming the Ninth Circuit’s decision in Siracusano v. Matrixx Initiatives, Inc., 585 F.3d 1167 (9th Cir. 2009). The Court held that plaintiffs adequately pleaded materiality and scienter, stating a claim under Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act and SEC Rule 10b-5, based on a pharmaceutical company’s nondisclosure of adverse event reports, even though the reports were not alleged to be statistically significant. Matrixx Initiatives, Inc. v. Siracusano, 131 S. Ct. 1309 (2011).

The Supreme Court’s decision resolves a split of authority between the Ninth Circuit and the First, Second, and Third Circuits, which previously had held that drug companies have no duty to disclose adverse event reports until those reports provide statistically significant evidence that the adverse events may be caused by, and are not simply randomly associated with, a drug’s use. See, e.g., N.J. Carpenters Pension & Annuity Funds v. Biogen IDEC Inc., 537 F.3d 35, 50 (1st Cir. 2008); In re Carter-Wallace, Inc. Sec. Litig., 220 F.3d 36, 41-42 (2d Cir. 2000); In re Carter-Wallace, Inc. Sec. Litig., 150 F.3d 153, 157 (2d Cir. 1998); Oran v. Stafford, 226 F.3d 275, 284 (3d Cir. 2000).

In Matrixx, the Supreme Court reaffirmed that the materiality requirement is satisfied when there is “a substantial likelihood that the disclosure of the omitted fact would have been viewed by the reasonable investor as having significantly altered the ‘total mix’ of information made available.” 131 S. Ct. at 1318 (quoting Basic Inc. v. Levinson, 485 U.S. 224, 231-32 (1988)). The Court reaffirmed Basic and declined to adopt a bright-line rule that adverse event reports relating to a company’s products are immaterial absent a statistically significant risk that the product is the cause of the adverse events. The Court held that such a rule would “artificially exclud[e]” information that would otherwise be considered significant to a reasonable investor’s trading decision. Id. at 1319 (quoting Basic, 485 U.S. at 236).

In declining to draw a bright-line test, the Court rejected Matrixx’s argument that statistical significance is the only reliable indication of causation, reasoning that statistically significant data is not always available (e.g., when an adverse event is subtle or rare) and that, in any event, “[a] lack of statistically significant data does not mean that medical experts have no reliable basis for inferring a causal link between a drug and adverse events.” Id. The Court emphasized that the FDA does not limit the evidence considered for purposes of assessing causation to statistically significant data, but instead relies on a wide range of evidence and “sometimes acts on the basis of evidence that suggests, but does not prove, causation.” Id. at 1320. Given that medical professionals and regulators act based on evidence of causation that is not statistically significant, the Court concluded that “in certain cases reasonable investors would as well.” Id. at 1321.

Notably, the Court emphasized that its holding “does not mean that pharmaceutical manufacturers must disclose all reports of adverse events.” Id. Rather, “[t]he question remains whether a reasonable investor would have viewed the nondisclosed information ‘as having significantly altered the “total mix” of information made available.'” Id. (quoting Basic, 485 U.S. at 232). The Court observed that the “mere existence” of adverse events reports will not satisfy this standard. Id. The Court’s test requires a contextual, case-by-case inquiry as to whether a reasonable investor would have viewed adverse event reports as material even in the absence of statistically significant evidence. Id.

While the Court rejected a bright-line test for materiality, the Court also reaffirmed that Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 do not create an affirmative duty to disclose material information. Rather, disclosure is required “only when necessary ‘to make . . . statements made, in the light of the circumstances under which they were made, not misleading.'” Id. (quoting 17 C.F.R. § 240.10b-5(b)). Thus, “[e]ven with respect to information that a reasonable investor might consider material, companies can control what they have to disclose under these provisions by controlling what they say to the market.” Id. at 1322. Matrixx had announced that Zicam revenues were going to rise 50 and then 80 percent and that “the reports indicating that Zicam caused anosmia were ‘completely unfounded and misleading’ and that ‘the safety and efficacy of [Zicam’s active ingredient] for the treatment of symptoms related to the common cold have been well established.'” Id. at 1323. In light of these statements, and the allegation that Matrixx did not have scientific evidence disproving the link between Zicam and anosmia, the Court held that defendants could not be silent about the reports they received about that possible link.

In a unanimous decision issued on June 6, 2011, the Supreme Court held in Erica P. John Fund, Inc. v. Halliburton Co., 131 S. Ct. 2179 (2011), that plaintiffs in a private securities fraud action are not required to prove the element of loss causation in order to obtain certification of a damages class under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23(b)(3).

To certify a class under Rule 23(b)(3), questions of law or fact common to class members must “predominate” over any questions affecting only individual members. Id. at 2184. In a securities fraud action, the predominance issue “often turns on the element of reliance.” Id. Under Basic, Inc. v. Levinson, 485 U.S. 224 (1998), plaintiffs are permitted to invoke a rebuttable presumption of reliance using the “fraud-on-the-market” theory, which presumes that the “‘market price of shares traded on well-developed markets reflects all publicly available information'” and, accordingly, that an “investor relies on public misstatements whenever he ‘buys or sells stock at the price set by the market.'” 131 S. Ct. at 2185 (quoting Basic, 485 U.S. at 244, 246-47)).

In a line of prior class certification decisions, the Fifth Circuit had held that, in order to invoke the Basic presumption at the class certification stage, plaintiffs were required to prove the element of loss causation–i.e., that the correction of a prior misleading statement (as opposed to other factors) caused the disputed decline in the price of the issuer’s stock. Id.

In Halliburton, the Supreme Court disagreed. Reaffirming Basic, the Court reasoned that the Fifth Circuit’s requirement “contravenes Basic‘s fundamental premise that an investor presumptively relies on a misrepresentation so long as it was reflected in the market price at the time of his transaction.” Id. at 2186. “[T]hat a subsequent loss may have been caused by factors other than the revelation of a misrepresentation,” the Court explained, “has nothing to do with whether an investor relied on the misrepresentation in the first place.” Id. In other words, loss causation and reliance address two different matters; whereas an investor presumptively relies on a defendant’s misrepresentation if that information is reflected in the stock’s market price, loss causation requires a plaintiff to show that a misrepresentation also caused a subsequent economic loss. Id. Because loss causation “has no logical connection to the facts necessary to establish the efficient market predicate to the fraud-on-the-market theory,” the Fifth Circuit erred in requiring the plaintiff to prove loss causation as a condition of obtaining class certification. Id.

The Court’s narrow holding in Halliburton leaves open many key questions, which may be the subject of future appeals to the Court. Indeed, the Court seems to have signaled that one such issue might be taken up in the future–specifically, whether, and how, a defendant may defeat the “fraud on the market” presumption of reliance at the class certification stage. The Court’s later decision in Wal-Mart (discussed in the next section) provides further grounds for securities class action defendants to attempt to defeat class certification, and to force plaintiffs to come forward with expert reports and other evidence to allow a court to conduct the “rigorous analysis” now required under Wal-Mart. For a further discussion of the interplay between Halliburton and Wal-Mart, please see a recent article by Mark A. Perry and Blaine H. Evanson, “Challenging the Presumption of Reliance on Class Certification after Halliburton and Wal-Mart,” Wall Street Lawyer (vol. 15, no. 8, August 2011).

Gibson Dunn filed an amicus brief on behalf of The American Insurance Association, AXIS Insurance Company, Continental Casualty Company, and HCC Global Financial Products in the Halliburton case, advocating for a different application of Rule 23 to the issue of loss causation, but the Court did not address this issue in light of its narrow ruling.

The Supreme Court’s much anticipated decision in the largest employment discrimination class action ever–litigated on behalf of Wal-Mart by Gibson Dunn–was handed down late this term. While most directly concerning class certification issues in the Title VII employment discrimination context, the decision does likely implicate securities fraud class actions.

For securities litigation, the most salient aspect of the Court’s decision is its ruling on the Rule 23(a)(2) commonality requirement, which applies to all class actions brought under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. The Court held that the claims of a class must “depend on a common contention” and “must be of such a nature that is capable of class wide resolution–which means that determination of its truth or falsity will resolve an issue that is central to the validity of each one of the claims in one stroke.” Slip op. at 9. It is not enough that all class members “suffered a violation of the same provision” of a statute. Id. This tightening of the commonality requirement could be relevant in securities fraud cases in which putative class members have different factual and legal bases for recovery, including, for instance, if class members relied on different statements made over a period of time.

Importantly, the Court confirmed that “Rule [23] does not set forth a mere pleading standard.” Plaintiff must affirmatively put on evidence demonstrating that they meet Rule 23’s requirements. Slip op. at 10. Securities fraud plaintiffs cannot merely allege that they are qualified to represent a class.

The Court again endorsed the “rigorous analysis” standard under which a district court must analyze class certification issues, and it acknowledged that such analysis will “frequently . . . entail some overlap with the merits of the plaintiff’s underlying claim. That cannot be helped.” Slip op. at 10 n.6. As an example of this overlap, the Court cited the requirement that plaintiffs in securities class actions prove that their shares traded on an efficient market. They must make that showing, the Court explained, at the class certification stage to invoke the “fraud on the market” presumption, which enables them to avoid proving reliance on an individual basis. Id. at 11 n.6. Yet “they will surely have to prove” the existence of an efficient market “again at trial in order to make out their case on the merits.” Id. In short, plaintiffs must prove that they satisfy all the elements of class certification, even if some elements go to the merits of their claims.[4]

Gibson Dunn represented Wal-Mart before the Supreme Court, and our partner Ted Boutrous argued the case before the Supreme Court.

In June 2011, the Court granted review in Credit Suisse Securities (USA) LLC v. Simmonds, No. 10-1261. The Court will consider the Ninth Circuit’s application of the two-year statute of limitations for claims brought under Section 16(b) of the Exchange Act, which prohibits corporate insiders from profiting through “short-swing” trading within a six-month period. Adhering to its own thirty-year-old precedent, the Ninth Circuit held that the limitations period for derivative claims under Section 16(b) is tolled until the defendant formally discloses his short-swing trades, even after the corporation on whose behalf the plaintiff is suing has actual notice of the facts giving rise to the Section 16(b) claims. By contrast, the Second Circuit holds that tolling under Section 16(b) ends as soon as the interested issuer or its shareholders have notice of the facts underlying such claims. The Supreme Court’s decision is expected to resolve this conflict and could have broader implications on the intersection between federal statutes of limitations and the application of equitable tolling principles in derivative lawsuits.

III. Jurisdiction Of U.S. Courts Over Claims Against Foreign Issuers After Morrison After the Supreme Court’s precedent-setting ruling in 2010 in Morrison v. National Australia Bank, 561 U.S. __, 130 S. Ct. 2869 (2010), lower courts have issued a series of new rulings in the first half of 2011 that interpret and apply Morrison.

In Morrison, foreign citizens sued a foreign issuer in the United States based on securities transactions that transpired in a foreign country–a fact pattern that commentators refer to as a “foreign-cubed” or “f-cubed” lawsuit. Id. at 2875. The Court concluded that Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act does not apply extraterritorially, and that the focus of the statute lies “not upon the place where the deception originated, but upon purchase and sale of securities in the United States.” Id. at 2884. The Court thus established a “transactional test,” holding that Section 10(b) applies only to “the purchase or sale of a security listed on an American stock exchange, and the purchase or sale of any other security in the United States.” Id. at 2884; see also id. at 2886 (describing the “transactional test” as “whether the purchase or sale is made in the United States, or involves a security listed on a domestic exchange”). In announcing the “transactional test,” the Court jettisoned the Second Circuit’s “conduct and effects” tests, which had previously been used to determine the extraterritorial effect of the securities and commodities laws.

Applying its new standard to the facts before it, the Court held that the plaintiffs failed to state a claim upon which relief could be granted under Section 10(b) because the purchase or sale of the securities at issue–ordinary shares of an Australian bank listed on an Australian exchange–“involve[d] no securities listed on a domestic exchange, and all aspects of the purchases complained of by those petitioners who still have live claims occurred outside the United States.” Id. at 2888.

Post-Morrison decisions in the first half of 2011 reflect at least three areas of continuing controversy over federal securities claims filed against foreign issuers in U.S. courts. We address each of them below.

First, courts have grappled with the question whether securities that were not listed on a U.S. exchange were nevertheless purchased or sold in the United States. Id. at 2884, 2886.

- In Quail Cruises Ship Management Ltd. v. Agencia de Viagens CVC Tur Limitada, —F.3d —, 2011 WL 2654004 (11th Cir. July 8, 2011), the court reversed the dismissal of a Section 10(b) suit on Morrison grounds, reasoning that a “sale” was “consummated” in the United States when the transaction for the acquisition of the stock “closed” in the United States, thereby triggering the transfer of title–or “sale”–of the shares in the United States.

- In SEC v. Goldman Sachs & Co., 2011 WL 2305988 (S.D.N.Y. June 10, 2011), the SEC brought claims against Fabrice Tourre pursuant to Section 17 of the Securities Act and Section 10(b). In his motion to dismiss, Tourre argued that the SEC could not meet its burden under Morrison to demonstrate that the various transactions at issue took place in the United States. The SEC countered that: (1) Goldman Sachs and Tourre operated in New York; (2) Tourre offered the securities and related security-based swaps to investors through false and misleading statements in New York; and (3) Tourre promoted and solicited participation in the securities transaction in New York. The court sided with Tourre. The court reasoned that at the core of both a “sale” and a “purchase” is the notion of “irrevocable liability”–i.e., a buyer incurs irrevocable liability at some point to take and pay for a security, and a seller incurs irrevocable liability at some moment to deliver a security. Because none of the U.S.-based conduct–including emails sent from the U.S. soliciting the purchase of securities–showed that any party incurred irrevocable liability in the U.S., the court dismissed the SEC’s Section 10(b) claim. (The court also dismissed the Section 17(a) claim insofar as it alleged “sales” outside the United States (as opposed to “offers,” to which Section 17(a) applies)). Id. at *9-14. Recognizing the absence of “irrevocable liability” in the U.S.-based conduct, the SEC urged the court to look at the “the entire selling process” in determining the location of a transaction, but the court rejected this approach as merely “an invitation . . . [to] return to the ‘conduct’ and ‘effects’ tests” repudiated in Morrison. Id. at *9.Two additional points are worth noting. First, in apparent disagreement with the Eleventh Circuit in Quail Cruises, supra,the court specifically rejected the argument that the “closing” of a transaction, absent a “‘purchase or sale . . . made in the United States,'” is sufficient to make the purchases of securities domestic transactions under Morrison. Id. And second, the court declined to consider Tourre’s argument that the “trade confirmations are sufficient to establish the territorial location of a ‘purchase’ or ‘sale.'” Id. at *10.

- In Cascade Fund, LLP v. Absolute Capital Management Holdings Ltd., 2011 WL 1211611 (D. Colo. Mar. 31, 2011), the court dismissed a Section 10(b) case against a defendant fund manager because the transaction was not “completed” in the United States. Id. at *7. The plaintiff argued that four facts were indicative of a domestic transaction: (1) the offering memoranda was disseminated to the plaintiff in the United States; (2) members of the defendant company traveled to the United States to solicit American investors; (3) the plaintiff made its decision to invest while in the United States; and (4) the money for the purchase was wired to a bank in the United States. Id. The court rejected these facts as “insufficient to deem the locus of the transaction to be the United States.” Id. As to the first three facts, the court noted that Morrison “strongly suggests that inquiry into the location of solicitation [or to “events preparatory to th[e] transaction”] [are] irrelevant to the inquiry.” Id. (emphasis added). And as to the fourth, the court concluded that a wire transfer “was not sufficient to complete the transaction,” and thus “the transaction was not completed until ACM [the defendant] finally accepted an application–presumably in its Cayman Islands offices.” Id.

- In In re Optimal U.S. Litigation, — F. Supp. 2d —-, 2011 WL 1676067 (S.D.N.Y. May 2, 2011), the court concluded that plaintiffs’ allegation that purchases and sales of shares of the defendant company “took place in the United States” was sufficient to withstand a motion to dismiss. Id. at *12. Defendants argued that this allegation was belied by the prospectus, which (1) directed fund purchasers to send their subscription forms to the fund’s administrator in Ireland; (2) made clear that directors could defer acceptance of such subscription until all monies cleared; and (3) the sale of the shares became final only when the fund’s administrator accepted the subscription form. Id. at *11. Plaintiffs did not contest that “acceptance” of the subscription forms occurred in Ireland, but they argued that the shares were “purchased” where they were issued–i.e., in New York–a fact evidenced by the contract notes issued to shareholders, which stated: “WE BOUGHT [SOLD] FOR YOUR ACCOUNT IN: NYS.” Id. at *12. The court concluded: “Drawing all reasonable inferences in Plaintiffs’ favor, the Contract Notes support Plaintiffs’ allegation that the purchases . . . ‘took place in the United States.'” Id. Moreover, the court found defendant’s argument “better-suited for . . . summary judgment in the context of a more fully-developed factual record that unequivocally establishes where all of Plaintiffs’ shares were ‘issued,’ where they wired their subscription payments, what the statement [in the contract notes] . . . means, and where their subscription agreements were ‘accepted.'” Id.

Second, courts have been asked to determine whether plaintiffs who purchased shares listed on foreign exchanges may nonetheless assert Section 10(b) claims in the United States merely because the issuer lists some other shares on a U.S. exchange. So far in 2011, courts appear to be unpersuaded by this “listing” argument. See In re Royal Bank of Scotland Grp. PLC Sec. Litig., 765 F. Supp. 2d 327, 336 (S.D.N.Y. 2011) (rejecting plaintiffs’ theory that a company’s U.S. listing subjects all transactions in the company’s shares to the U.S. securities laws regardless of where they take place); see id. (“The idea that a foreign company is subject to U.S. Securities laws everywhere it conducts foreign transactions merely because it has ‘listed’ some securities in the United States is simply contrary to the spirit of Morrison.”); In re Vivendi Universal, S.A. Sec. Litig., 765 F. Supp. 2d 512, 527-30 (S.D.N.Y. 2011) (concluding that a “foreign cubed” transaction does not survive Morrison where ordinary shares are listed but not traded on a domestic exchange as a result of a foreign issuer’s American Depository Receipt (ADR) program, reasoning that Morrison’s transactional test “turns on the territorial location of the subject transaction”). The Second Circuit recently declined to hear an interlocutory appeal of the Vivendi decision, reasoning that the decision is not related to class certification, is not clearly erroneous, and could be reviewed after the entry of final judgment.

Third, notwithstanding Morrison‘srepudiation of the “conduct and effects” test, at least one court has conducted the equivalent of that analysis where the alleged misconduct consisted of criminal securities fraud in combination with other criminal fraudulent schemes. In United States v. Mandell, 2011 WL 924891 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 16, 2011), the indictment alleged criminal securities fraud, conspiracy to commit criminal securities fraud, wire fraud, and mail fraud with respect to “Sky capital and other securities.” Id. at *4. Sky Capital is incorporated and headquartered in the United States, but its stock is traded on the London Stock Exchange. Id. at *1. The defendant argued that all portions of the indictment that “alleged fraud with regard to securities listed on foreign exchanges and/or occurring outside the United States must be dismissed” under Morrison. Id. at *3. The court disagreed. Without parsing the securities count from the mail and wire fraud counts, the court essentially conducted a “conduct and effects” analysis, noting, for example, that the defendant companies were organized in the United States; the money was controlled in the United States; and the schemes were “orchestrated from and occurred here in the United States.” Id. at *4. “There is no apparent reason,” the court concluded, “why the fraudulent and manipulative schemes charged here should not be prosecuted because some trades, which were actually part of the fraudulent and manipulative schemes, were executed on a foreign exchange.” Id. at *5. This decision signals the potential difficulty in applying Morrison to multi-count indictments alleging wide-ranging fraudulent schemes.

As we reported in our Year-End Securities Litigation Update, Congress responded to Morrison by enacting Section 92P(b) of the Dodd-Frank Act, which attempts to restore the extraterritorial application of the antifraud provisions of the federal securities laws in SEC and DOJ enforcement actions. Effective as of July 21, 2010, federal courts have jurisdiction in any action brought by the SEC or DOJ involving (1) “conduct within the United States that constitutes significant steps in furtherance of the violation, even if the securities transaction occurs outside the United States and only involves foreign investors,” or (2) “conduct occurring outside the United States that has a foreseeable substantial effect within the United States.” In addition, Section 929Y of the Act instructs the SEC to solicit public comments and to conduct a study to determine the extent to which private litigants should be allowed to sue for transnational securities fraud under Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act. Since issuing a call for comments on October 25, 2010, see Study on Extraterritorial Private Rights of Action, SEC Release No. 34-63174, available at www.sec.gov/rules/other/2010/34-63174.pdf, the SEC has received numerous letters from interested parties advocating for and against extension of the private action under Section 10(b) to transnational securities fraud. The SEC is required to submit the results of its study to the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs of the Senate and the Committee on Financial Services of the House by January 21, 2012.

IV. “Credit Crisis” Litigation

Although the total number of new securities litigation filings has increased over last year, the pace of new filings related to the “credit crisis” continued to decline during the first half of 2011, with only 8 such filings as reported by NERA Economic Consulting. Nonetheless, there have been a number of significant developments in pending cases this year:

- Courts continue to hold that plaintiffs lack standing to sue over offerings in which they did not invest. One court applied this limitation to litigation arising from mortgage-backed securities (“MBS”), to hold that “[p]laintiffs must establish that they have tranche-based standing as to the securities involved here.” Me. State Ret. Sys. v. Countrywide Inc., No. 10-302, slip op. at 4 (C.D. Cal. May 5, 2011). As part of its analysis, the court focused on the differences in the loan pools collateralizing the separate tranches of an offering, finding that a plaintiff has not suffered any cognizable injury with respect to tranches in which he or she had not invested. Id. at 13 (“The key to the standing issue is the significant differences between the underlying pools of mortgages.”). Accordingly, there can be no constitutional or statutory standing as to tranches in which a plaintiff has not purchased. Id. at 12 (“[T]he plain text of the Securities Act dictates that Plaintiffs must have acquired or purchased the security on which they sue[, and] [i]t is undisputed that each [tranche] is a separate security.”).

- In Plumbers’ Union Local No. 12 Pension Fund v. Nomura Asset Acceptance Corp., 632 F.3d 762, 773 (1st Cir. 2011), the First Circuit reversed a district court’s dismissal, holding that, where plaintiffs allege “wholesale abandonment” of underwriting guidelines, disclosures in offering materials that the underwriting standards for the underlying loans were less stringent than those used by Fannie Mae, and that exceptions occur when borrowers demonstrate other “compensating factors,” were insufficient to require dismissal. See also Employees’ Ret. Sys. of the Gov’t of the V.I. v. J.P. Morgan Chase & Co., 2011 WL 1796426 (S.D.N.Y. May 10, 2011) (denying motion to dismiss where plaintiffs alleged that the offering material for eleven offerings of MBS failed to disclose that the underwriters had effectively abandoned their own underwriting guidelines).

- As reported in our Year-End Securities Litigation Update, on December 1, 2010, a jury found for defendants on most counts in Hubbard v. BankAtlantic Bancorp, Inc., No. 07 cv 61542 (S.D. Fla. filed Oct. 29, 2007), but decided that Bancorp and BankAtlantic’s former Chairman and CEO violated Section 10(b) by making a misleading comment during a conference call with investors. On April 25, 2011, however, the court granted defendants’ motion for judgment as a matter of law with respect to all claims and statements, and denied conditionally defendants’ motion for a new trial. See In re BankAtlantic Bancorp., Inc. Sec. Litig., 2011 WL 1585605 (S.D. Fla. Apr. 25, 2011). The court granted judgment as a matter of law because the “evidence of loss causation or damages was insufficient” as to the alleged misrepresentation found by the jury. Id. at *8.

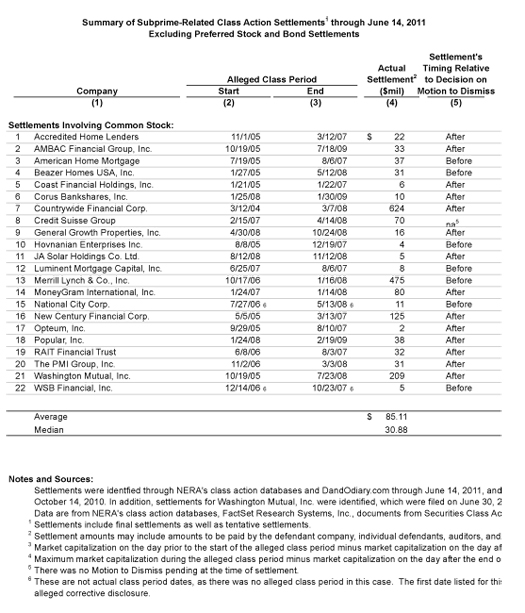

Settlements related to the “credit crisis” have proven to be substantially larger than other securities class action settlements. According to one report, through the end of 2010, settlements of securities class actions arising from the credit crisis ranged in size from $4.0 million to $624 million, averaging $103.1 million, with a median value of $31.3 million. The average settlement value during the same period for securities class actions that were unrelated to the credit crises was $31.6 million, with a median value of $10 million. See Ellen M. Ryan & Laura E. Simmons, Cornerstone Research, Securities Class Action Settlements: 2010 Review and Analysis, March 15, 2011, at 12, available here.

Although the number of new credit crisis filings has waned, the number of settlements increased during the first half of 2011, with 10 settlements compared to only 8 settlements in all of 2010. A mid-2011 private study of recent settlements by NERA Economic Consulting portrays the credit crisis settlement trends as follows:

As indicated in the table, the listed credit crisis settlements through June 14, 2011 reflect that the median credit crisis settlement was $30.88 million, translating to 2.02% of investor losses, and 1.81% of pre-post market capitalization drops for the issuers in question. Similarly, the average settlement was $85.11 million, translating to 2.96% of investor losses, and 12.13% of pre-post market capitalization drops.

There are approximately 140 pending cases that have not yet been dismissed or resolved. Securities Class Action Services Alert: Settlements of Credit-Crisis Lawsuits on the Rise, Institutional Shareholder Services (June 2011). Thus, the number of settlements should continue to increase over the next year as actions filed in 2008 and later mature.

V. SLUSA and CAFA The first half of 2011 has generated several opinions concerning the definition of “covered securities” under the Securities Act, 15 U.S.C. § 77r(b)(1), which directly affects the scope of preclusion and jurisdiction under the Securities Litigation Uniform Standards Act (“SLUSA”) and the Class Action Fairness Act (“CAFA”).

In a bondholder class action pleaded under state law, the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California held that the claims involved “covered securities” and therefore were precluded under SLUSA, even though the bonds–notes issued by Toyota Motor Corp.–were traded exclusively on foreign exchanges. Harel Pia Mut. Fund v. Toyota Motor Corp., No. 10-cv-06871 DSF (AJWx) (C.D. Cal. Jan. 10, 2011). The plaintiffs had argued that the bonds were not “covered securities” because the provisions that define that term include a heading that refers to “nationally traded” securities. Plaintiffs argued that “nationally traded” securities could not mean securities traded overseas. See 15 U.S.C. § 77r(b)(1). As Toyota successfully countered, however, the Securities Act specifically defines “covered securities” to include those that are “equal in seniority or . . . senior . . . to” the same issuer’s other securities that are traded on U.S. exchanges (as were Toyota’s bonds). See 15 U.S.C. § 77r(b)(1)(C).

Relying on Morrison v. National Australia Bank, Ltd., 130 S. Ct. 2869 (2010), the plaintiffs contended that SLUSA should not apply “extraterritorially” to preclude claims concerning foreign-traded securities. The court was unconvinced. Although the court did not address Morrison explicitly, its decision in favor of Toyota was consistent with Toyota’s position that construing SLUSA to preempt state-law claims based on foreign-traded securities did not violate the presumption against the extraterritoriality.

The U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York reached a similar result, concluding that investors in a Madoff case brought claims concerning “covered” securities that were preempted by SLUSA, even though the claims arose from shares in overseas funds. In re Kingate Mgmt. Ltd. Litig., 2011 WL 1362106, at *7 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 30, 2011). The court reasoned as follows:

Plaintiffs’ argument that the logic of Morrison bars the application of SLUSA to the current action may be swiftly dispatched. . . . SLUSA, by its terms, applies to class actions in State and Federal courts of the United States, 15 U.S.C. § 8bb(f)(1), and is applied here to a class action in a court of the United States. SLUSA is not being applied extraterritorially in this matter, and the logic of Morrison therefore has no effect on SLUSA’s applicability.

In another class action brought by investors in Toyota’s foreign-traded common stock and domestically-traded American Depository Shares (ADSs), the court held that the common stock was a “covered” security and therefore fell within the “securities” carve-out to jurisdiction under the Class Action Fairness Act, 28 U.S.C. § 1332(d)(9). In re Toyota Motor Corp. Sec. Litig., No. 10-cv-00922 DSF (AJWx) (C.D. Cal. July 7, 2011). The analysis was similar as in the Harel Pia matter. Again, the plaintiffs relied upon the “nationally traded” heading in the definition of covered securities. And again, they were thwarted by a substantive provision–one providing that securities are covered so long as they are “listed” on a national exchange. See 15 U.S.C. § 77r(b)(1)(A). The disputed common stock was listed–though not traded–to facilitate trades of the ADSs.

Because there was no jurisdiction under CAFA, the court lacked original jurisdiction over claims concerning the foreign-traded common stock. (Plaintiffs relied on foreign law in an attempt to evade Morrison‘s holding that Section 10(b) does not extend to foreign-traded securities and Morrison‘s clear implication that merely being listed on a domestic exchange is not enough when the transactions at issue took place overseas.). And although the court concluded that it could exercise supplemental jurisdiction over those claims because the claims concerning the common stock were transactionally related to the claims concerning the domestically-traded ADSs, it declined to do so because (1) the capitalization under the common stock far exceeded that under the ADSs such that the claims on the common stock would “substantially predominate[]” and (2) considerations of comity to Japanese courts–as reflected by the Supreme Court’s discussion in Morrison–constituted “compelling reasons” for declining jurisdiction.

Finally, the California Court of Appeal has split from other courts by holding that “covered class actions” raising state claims involving non-covered securities remain with the state courts’ concurrent jurisdiction after SLUSA. Luther v. Countrywide Fin. Corp., 195 Cal. App. 4th 789 (May 18, 2011). Several courts have held that SLUSA preempts state jurisdiction in such matters, because Section 22(a) of the Securities Act, 15 U.S.C. § 77v(a), precludes jurisdiction over “covered class actions” as that term is defined in Section 16 of the Act, without also requiring a connection to “covered securities.” See, e.g., Knox v. Agria Corp., 613 F. Supp. 2d 419 (S.D.N.Y. 2009); In re Fannie Mae 2008 Sec. Litig., Nos. 08 Civ. 7831(PAC), 09 Civ. 1352 (PBAC), 2009 WL 4067266 (S.D.N.Y. Nov. 24, 2009). The California Court of Appeal declined to follow these cases, distinguishing them as concerning only the question of removal under SLUSA, as opposed to the scope of state-court jurisdiction. The defendants in this matter (including the underwriter defendants, represented by Gibson Dunn) have petitioned for review to the California Supreme Court.

VI. Important Class Certification Rulings There have been several important rulings on class certification issues in the last six months. As discussed above, in Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Dukes, the Supreme Court outlined significant changes to Rule 23(a)(2)’s commonality requirements and confirmed the trend developing in the Courts of Appeals towards tightening the standards for class certification generally. The Supreme Court also ruled narrowly on class certification issues in the Halliburton case, leaving much unresolved in its wake.

A. “Price Impact” Arguments Against the Fraud-on-the-Market Presumption

Halliburton presented an opportunity for the Court to clarify and even revisit the fraud-on-the-market presumption outlined in Basic v. Levinson. But the Court chose to decide the case on narrow grounds, and did not reach this issue. Indeed, the Court declined to “address any other question about Basic, its presumption, or how and when it may be rebutted.” 131 S. Ct. at 2187. It specifically declined Halliburton’s offer to express an opinion as to how evidence of “price impact”–a common piece of rebuttal evidence offered by securities fraud defendants–fits within the Basic framework. As such, the Court’s narrow holding will likely have little impact outside of the Fifth Circuit–the only circuit that required a plaintiff to prove loss causation to invoke the presumption. In other words, the court did not meaningfully advance the law as to how securities fraud defendants can rebut the fraud-on-the-market presumption.

While the Supreme Court declined to address how securities fraud defendants can rebut presumption of reliance at the class certification stage, the Third Circuit provided a fairly detailed analysis of this exact issue in In re DVI Sec. Litig., 639 F.3d 623 (3d Cir. 2011). The court largely adopted the Second Circuit’s approach in In re Solomon Analyst Metromedia Litig., 544 F.3d 474 (2d. Cir. 2008), that a securities fraud defendant can rebut the presumption by the showing the absence of price impact from the alleged misrepresentations. 639 F.3d at 638. The court concluded that the absence of price impact undermines the presumption for several reasons, such as suggesting the lack of market efficiency and the lack of materiality of the alleged misstatements. Id. Specifically, the court concluded that a defendant can rebut the presumption by showing the lack of price impact at the time of the curative disclosure. Id.

In our view, the price impact analysis is not undermined by the Supreme Court’s decision in Halliburton, although plaintiffs may attempt to argue otherwise. As noted above, the Court expressly stated that it would not address the defendants’ “price impact” argument in Halliburton, as it had not been considered by the Fifth Circuit; rather, the Court said, defendants were free to re-argue the “price impact” issue on remand of the case to the Fifth Circuit. We will follow the Halliburton remand with interest, to see how the “price impact” issue is addressed in future proceedings.

On March 31, 2011, the Southern District of New York reaffirmed that securities fraud defendants can rebut the fraud-on-the-market presumption by presenting evidence that the alleged misstatements had no effect on the price of the issuer’s stock. See In re Moody’s Corp. Securities Litigation, 2011 WL 1237690, at *6-*11 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 31, 2011). In In re Moody’s, the defendants’ expert conducted an “event study” demonstrating that none of the alleged misstatements was associated with a statistically significant, positive change in Moody’s stock price; the event study further showed that no disclosure correcting those misstatements (at least none that occurred during the class period) was associated with a statistically significant, negative change. Id. at *9. Although the plaintiffs’ expert identified certain disclosures that were purportedly connected to a negative price change, those disclosures either were not truly corrective (since they did not contain new information), were made outside the class period, or were insufficiently linked to a price impact (since they were statistically significant at the 90% confidence level, rather than the conventional 95% confidence level). Id. at 10 & n.11. Since there was “no period within the proposed class period where the alleged misrepresentation caused a statistically significant increase in the price or where a corrective disclosure caused a statistically significant decline in the price,” the court held that the defendants had “successfully rebutted” the “the reliance presumption.” Id. The court, therefore, denied class certification. Id.

On April 14, the plaintiffs moved for leave to appeal to the Second Circuit under Rule 23(f) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. On June 6, the Supreme Court decided Halliburton, and the plaintiffs filed a notice of that decision with the Second Circuit shortly thereafter. On July 21, a three-judge panel denied the interlocutory appeal in short order saying only that “immediate appeal is unwarranted.” This decision might signal that substantial uncertainty remains in the wake of Halliburton about how defendants can rebut the fraud-on-the-market presumption in cases where there is no statistically significant connection between the alleged securities fraud and any impact on stock price.

When the plaintiff moved for certification of a class of bondholders in In re Dynex Capital Securities Litigation, the court in dicta suggested that market efficiency should be analyzed differently in the context of bond markets. In re Dynex Capital Sec. Litig., 2011 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 22484, at *12 (S.D.N.Y Mar. 7, 2011). The court applied the so-called “Cammer” test, which is the five-factor test the Second Circuit adopted in Teamsters Local 445 Freight Division Pension Fund v. Bombardier, Inc., 546 F.3d 196 (2d Cir. 2008) to determine whether a market is efficient. In analyzing conflicting expert testimony about the first factor, namely trading volume, the court observed that the Second Circuit “suggested that the Cammer factors be adjusted in the context of bond markets” because bonds are traded less frequently than stocks. Id. at *13. Nevertheless, the court held that low trading volume alone does not defeat a finding of an efficient market, even in a market for stock. Id. at *14. In view of the other Cammer factors, the court concluded that the market for the bonds was efficient and certified the proposed class. Id. at *13-*19.

VII. Other Major Issues Addressed By Trial Courts on Motions to Dismiss and Summary Judgment

Although the Supreme Court’s decision in Erica P. John Fund, Inc. v. Halliburton Co. is undoubtedly the most important development this year in the law of loss causation, several other developments also are noteworthy.

First, courts increasingly are requiring plaintiffs who rely on a “leakage” approach to loss causation based on a series of partial disclosures to show that the partial disclosures “relate back” to the alleged misrepresentations. In 2009, the Tenth Circuit concluded in the context of a summary judgment motion that a corrective disclosure “must at least relate back to the misrepresentation and not to some other negative information about the company.” See In re Williams Sec. Litig.–WCG Subclass, 558 F.3d 1130, 1140 (10th Cir. 2009). This year, relying on Williams, the Fourth Circuit reached a similar conclusion, albeit at the initial pleadings stage. In Katyle v. Penn National Gaming, Inc., 637 F.3d 462(4th Cir. 2011), the Fourth Circuit stated: “Such [corrective] disclosures need not precisely identify the misrepresentation or omission; nor need the disclosure emanate from any particular source. But they must reveal to the market in some sense the fraudulent nature of the practices about which a plaintiff complains.” Id. at 473 (internal citation omitted). Because the allegedly corrective disclosures “did not even inferentially suggest that Penn’s prior press releases were fraudulent,” the court held, the district court properly granted the defendant’s motion to dismiss for failure to plead loss causation. Id. at 475, 478; see also In re Nuveen Funds/City of Alameda Sec. Litig., Nos. C 08-4575, C 09-1437, 2011 WL 1842819, at *10 (N.D. Cal. May 16, 2011) (quoting In re Williams Sec. Litig., 558 F.3d at 1139-40).

The Second Circuit followed a similar approach in Amorosa v. AOL Time Warner Inc., 409 F. App’x 412, 2011 WL 310316 (2d Cir. Feb. 2, 2011), rejecting plaintiff’s corrective-disclosure theory because none of the alleged corrective disclosures in any way addressed or implicated the allegedly fraudulent statements at issue–i.e., an auditor’s opinion about a company’s financial statements. Id. at *2. The court also rejected the plaintiff’s “materialization of the risk” theory because the plaintiff’s complaint neither referred to any misstatements by the auditor nor connected any fraud at the company to the auditor itself. Id. at *3.

Second, several courts held this year that once a plaintiff pleads a substantial causal link between the defendant’s fraud and the value of the company’s stock, questions about additional potential causes behind the securities’ decline in value do not ordinarily merit dismissal at the pleading stage. For example, in Hawaii Ironworkers Annuity Trust Fund v. Cole, 2011 WL 1257756 (N.D. Ohio Mar. 31, 2011), the court concluded that a complaint “need only show that the corrective disclosure was a substantial cause of the loss, not the only cause.” Id. at *14. Thus, because the plaintiff alleged that defendant’s stock price fell following two corrective press releases, both of which referred to defendant’s alleged inappropriate accounting practices, he was not required at the motion-to-dismiss stage to discern the weight given to other intervening factors, since that calculation was best left for a damages inquiry. Id. Similarly, in White v. Kolinsky, 2011 WL 1899307 (D.N.J. May 18, 2011), the court refused to dismiss plaintiffs’ complaint despite defendant’s argument that the intervening real estate crisis caused plaintiffs’ loss. Id. at *8. “While the real estate crisis and the broader economic climate may be relevant to [the] ultimate causation inquiry,” the court observed, “Defendants have not met their burden on this motion [to dismiss] of demonstrating that it was the sole, or even primary, factor in causing Plaintiffs’ losses.” Id.; see also Centaur Classic Convertible Arbitrage Fund Ltd. v. Countrywide Fin. Corp., 2011 WL 2504637, at *4 (C.D. Cal. June 21, 2011) (“Whether or not Plaintiffs can prove that the alleged corrective disclosures caused the drop in the [value of the securities] as opposed to macroeconomic events [such as the real estate market and subprime mortgage industry collapse], is a factual question that cannot be resolved at the motion to dismiss stage.”); In re Cell Therapeutics, Inc. Class Action Litig., 2011 WL 444676, at *6 (W.D. Wash. Feb. 4, 2011).

By contrast, at the summary-judgment stage, courts have been less willing to find a genuine issue of material fact where a plaintiff cannot disaggregate the allegedly corrective disclosure from other potential causes of plaintiff’s loss, particularly where the corrective disclosure is released simultaneously with multiple other pieces of negative news. For example, in In re BankAtlantic Bancorp, Securities Litigation, 2011 WL 1585605 (S.D. Fla. Apr. 25, 2011), the court found the plaintiff’s proof of loss causation insufficient because the plaintiff was unable to disaggregate the effects of the alleged corrective disclosure from other negative news revealed at the same time, and the plaintiff’s expert testimony was insufficient to separate the effects of multiple pieces of information. Id. at *19-21. Likewise, in In re Nuveen Funds/City of Alameda Securities Litigation, 2011 WL 1842819 (N.D. Cal. May 16, 2011), the court held that the plaintiffs failed to raise a triable issue of fact as to loss causation in part because their expert witness failed to conduct any investigation or analysis to support his conclusion that plaintiffs’ losses were caused by defendant’s fraud as opposed to non-fraudulent factors. Id. at *8.

Third, a division of district court authority appears to be emerging over whether plaintiffs in Section 11 cases involving mutual funds can establish loss causation. These cases follow a basic fact pattern: A mutual fund whose price is determined by a statutory index and not by active management conceals the risk of its holdings in its public statements, and at some later point, the value of the shares plummets because the fund’s actual risk materializes. On one side of the split, district courts in the First and Ninth Circuits have found proof of loss causation to be sufficient on a “materialization of the risk” theory, reasoning that the fund’s risk factor is the concealed risk, and the crash is the materialization. See In re Evergreen Ultra Short Opportunities Fund Sec. Litig., 705 F. Supp. 2d 86 (D. Mass. 2010); In re Charles Schwab Corporate Sec. Litig., 257 F.R.D. 534 (N.D. Cal. 2009).In contrast, the Southern District of New York held this year that because a mutual fund’s share value was determined by a statutory index as opposed to by market securities trading, it was impossible for the corrective disclosure to artificially inflate the fund’s value. See In re State St. Bank & Trust Co. Fixed Income Funds Inv. Litig., 2011 WL 1206070, at *5-9 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 31, 2011).

To establish liability under Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5, a plaintiff must prove that the defendant acted with scienter–i.e., a wrongful state of mind. Moreover, under the PSLRA, to plead a viable claim, a plaintiff is required to “state with particularity facts giving rise to a strong inference that the defendant acted with the required state of mind.” Although the scienter element of Section 10(b) claims remains a hurdle for plaintiffs, application of the holistic approach described in Tellabs continues to impact defendants at all levels. Courts issued the following noteworthy decisions in the first half of 2011:

- The United States Supreme Court in Matrixx Initiatives, Inc. v. Siracusano, 131 S. Ct. 1309 (2011), rejected defendants’ proffered bright-line rule requiring an allegation of statistical significance to establish the requisite strong inference of scienter. Id. at 1319. According to the Court, the allegations, “‘taken collectively,’ give rise to a ‘cogent and compelling’ inference that Matrixx elected not to disclose the reports of adverse events not because it believed they were meaningless, but instead because it understood their likely effect on the market.” Id. at 1324-25 (quoting Tellabs, Inc. v. Makor Issues & Rights, Ltd., 551 U.S. 308, 324 (2007)). Because such inference was at least as compelling as any competing inference from the facts alleged, the Court held that plaintiffs adequately pleaded scienter under the PSLRA. Id. at 1323-24.

- The Sixth Circuit in Frank v. Dana Corp., — F.3d —, 2011 WL 2020717 (6th Cir. May 25, 2011), reversed the district court’s dismissal of a securities and found that the plaintiff adequately plead scienter. Applying a holistic approach, the Court of Appeals found that the defendants’ optimistic statements leading up to the issuers bankruptcy. In light of the defendants’ receipt of internal reports and knowledge of overall industry problems and the collapse of the economy, the court found that “the inference that [the defendants] recklessly disregarded the falsity of their extremely optimistic statements is at least as compelling . . . as their excuse of failed accounting systems.” Id. at *6. The court analyzed the scienter allegations collectively and explained that reviewing individual allegations “is an unnecessary inefficiency” that “risks losing the forest for the tress.” Id. at *5.

- In New Mexico State Investment Council v. Ernst & Young LLP, 641 F.3d 1089 (9th Cir. 2011), the Ninth Circuit reversed the district court’s dismissal of a securities claim against an outside auditor. The Court of Appeals found a strong inference of scienter where the auditor was alleged to have known of improprieties concerning backdated stock options in 2000 and 2001, as well as corrective reforms taken in 2003. At issue was a 2005 unqualified audit opinion that covered the time period 2003 through 2005. The auditor defendant argued that because the plaintiff had not shown that the personnel who participated in the 2005 audit were aware of the earlier alleged backdating, the plaintiffs were attempting to apply “roving scienter” by combining knowledge of separate groups of individuals to plead an inference of scienter. Id. at 1099. The court rejected that argument, stating that because the defendant served as auditor from 1998 through 2008, it cannot “now disclaim those prior opinions simply because the same individuals were not involved.” Id. at 1100.

- In Staehr v. Mack, 2011 WL 1330856 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 31, 2011), the court granted defendants’ motion to dismiss a shareholder derivative action against current and former directors and officers of Morgan Stanley to recover losses arising from the company’s exposure to the subprime securities market. Id. at *7 . The court found that that mere allegations that “[d]irectors ‘were privy’ to unspecified internal research reports, that the acquisition of a subprime mortgage originator meant that the Board ‘must have understood’ the risks involved in the subprime mortgage industry, and that the publication of news reports on the subprime market meant that Defendants ‘must have been aware’ that the Company’s subprime assets were troubled” were “hardly sufficient” to establish an inference of scienter. Id.

- In In re Wachovia Equity Securities Litigation, 753 F. Supp. 2d 326, 361-62 (S.D.N.Y. 2011), the court declined to infer scienter from plaintiffs’ allegations that the defendant bank had engaged in GAAP violations by understating loan loss reserves. The court held that “[i]n the absence of particularized allegations that Wachovia was experiencing or internally predicting losses exceeding their set reserves, the subsequent disclosures provide no basis to conclude that Defendants recklessly misstated previous reserve levels.” Id. at 362.

C. Use of “Confidential Witnesses” to Plead Securities Fraud

Although courts in 2011 continued to allow the use of confidential witnesses as an appropriate source of pleading securities fraud, they also continue to express skepticism toward such allegations and to dismiss complaints that failed to plead particularized facts supporting the confidential witness’s purported knowledge of the information alleged.

- In Wachovia Equity Securities Litigation, 753 F. Supp. 2d 326 (S.D.N.Y. 2011), for example, the court dismissed several putative securities fraud class action complaints for failure adequately to plead scienter, reasoning that plaintiffs had not alleged that any of the confidential witnesses “made any personal contact with [the defendants] during the Class period,” and that most of the allegations drawn from confidential witnesses were “undated or pegged to an indefinite time period.” Id. at 352.

- In Coventry Healthcare, Inc. Securities Litigation, 2011 WL 1230998 (D. Md. Mar. 30, 2011), the court dismissed large portions of a putative class action complaint in part because all but one of the confidential sources were not alleged to have had any direct contact with the defendants or to possess any direct knowledge of what defendants allegedly knew or recklessly disregarded. Id. at *5-6.

- In Glaser v. The9, Ltd., 2011 WL 1106713 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 28, 2011), the court dismissed a complaint in part because three of the four confidential witnesses lacked any contact with any of the defendants, id. at *17, and the allegations as to the fourth witness did not specify the degree, kind, or context of his access to defendants–thereby “undermining the likelihood that he had personal knowledge of his allegations,” id. at *18.

- In Szymborski v. Ormat Techs., Inc., 2011 WL 835526, at *8 (D. Nev. Mar. 3, 2011), the court granted the defendant’s motion to dismiss in part because the evidence of falsity was based on a confidential witness who neither worked for the defendantnor had any direct contact with the defendants.

- In Mishkin v. Zynex Inc., 2011 WL 1158715 (D. Colo. Mar. 30, 2011), the court denied defendants’ motion to dismiss because the confidential witnesses actually were alleged to have personal knowledge of facts directly relevant to the allegedly fraudulent scheme, and the complaint specified the basis of that knowledge, their exposure to the relevant conduct, and the relevant time frame. Id. at *6-7.

- The court in Local 731 I.B. of T. Excavators and Pavers Pension Trust Fund v. Swanson, 2011 WL 2444675 (D. Del. June 14, 2011), also denied defendants’ motion to dismiss because plaintiffs alleged the “who, what, when, where and how about . . . [the] confidential informants and the basis of their knowledge.” Id. at *7 (internal quotation omitted).

- Skepticism toward the use of confidential witnesses proved to be well-founded in one case in which a confidential witness denied providing the information attributed to him in a complaint. City of Livonia Employees’ Retirement System v. Boeing Co.,2011 WL 824604 (N.D. Ill. Mar. 7, 2011). After the witness testified at his deposition that he was not the source for that information, the court granted reconsideration of the defendants’ motion to dismiss and dismissed the case with prejudice. Id. at *5. As the court explained:

If these facts were disclosed while the dismissal motions were pending, the court would not have concluded that the confidential source allegations were reliable, much less cogent and compelling. The second amended complaint would have been dismissed, possibly with prejudice, as insufficient under the PSLRA. It matters not whether, as plaintiffs argue, [the confidential witness] told their investigators the truth, but he is lying now for ulterior motives. The reality is that the informational basis for [the confidential witness allegations] is at best unreliable and at worst fraudulent, whether it is [the confidential witness] or plaintiffs’ investigators who are lying.

The Supreme Court’s decision in Matrixx, discussed above, was the most significant decision this year on the subject of pleading materiality, and essentially rejected defendants’ arguments advocating for a “quantitative” materiality standard. Early applications of Matrixx are beginning to show considerable uncertainty over how to apply the Supreme Court’s new standards.

- In Hill v. Gozani, — F.3d —, 2011 WL 2566143 (1st Cir. May 26, 2011), the First Circuit affirmed the dismissal of a securities claim based on a company’s failure to disclose future problems with reimbursement for its medical devices where the company had received warnings from its internal experts. Distinguishing Matrixx, the Court of Appeals held that where the company disclosed the possible risk of reimbursement problems, it was not required to publicly disclose internal dissention regarding its practices.

- The Eight Circuit, in Minneapolis Firefighters’ Relief Association v. MEMC Electronic Materials, Inc., 641 F.3d 1023 (8th Cir. 2011), rejected a plaintiff’s argument–based on Matrixx–that the company’s pattern of disclosure created a duty of disclosure. The court held that even if such a claim could be inferred from Matrixx, it would only apply–if at all–in exceptional circumstances. Moreover, “[f]irms are entitled to keep silent about good news as well as bad news unless positive law creates a duty to disclose.” Id. at 1028.

VIII. SEC and DOJ Enforcement Trends There have been a number of noteworthy developments in the securities enforcement field over the last six-month period.

Enforcement actions filed in federal court remained generally consistent with previous years, although the number has remained lower from the height of SEC enforcement activity in 2009. In the first six months of this calendar year, for example, the SEC initiated 125 injunctive actions compared to 118 in 2010 and 167 in 2009. The number of defendants charged also remained generally consistent with recent years, with the exception of 2009. In the first six months of 2011, the SEC charged 265 defendants, which is largely in line with 2010 and 2008, when the SEC charged 333 and 347 defendants, respectively. This figure is down significantly from the peak of 527 defendants charged during the same period in 2009.

The SEC appears to have continued focusing its resources on investigating and ultimately litigating cases against financial institutions and senior executives, particularly in the areas related to insider trading, director conduct, and accounting fraud. With regard to insider trading, the SEC’s emphasis has continued with new charges stemming from the widespread investigation of trading linked to the Galleon Group and guilty verdicts against several defendants following trials, as well as further lawsuits pertaining to the “expert networks industry.” The SEC has also begun using its new enforcement powers under the Dodd-Frank Act, bringing an administrative action for insider trading charges against an individual. The SEC also remains focused on pursing actions in connection with the financial crisis. In particular, the SEC reached a significant settlement with JP Morgan Securities LLC concerning CDO-related disclosures. Finally, the Commission, for the first time, used a deferred prosecution agreement to resolve an Enforcement Division investigation as part of its cooperation initiative unveiled in January 2010.